Workshop – Communication, Language and Agency

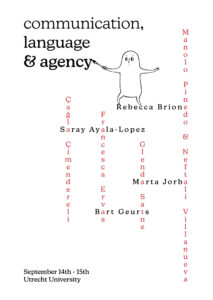

“Communication, Language and Agency”

14th and 15th of September

Utrecht University

Stijlkamer – Janskerkhof 13a, room 0.06

The workshop will be hybrid. If you would like to participate, please send an email to j.e.pascoe@uu.nl

We hope to see you there!

Program:

Thursday, 14th of September

9.30 – 10.00: Meet-up and coffee

10.00 – 10.15: Welcome and introduction

10.15 – 11.15: Francesca Ervas (University of Cagliari) – An experimental study on metaphors and epistemic injustice towards people with mental disorders (Remote talk)

11.30 – 12.30: Rebecca Brione (King’s College London) – Speech Acts, Silencing and Agency on the Maternity Ward: Understanding a Hidden Violation

12.30 – 14.30: Lunch

14.30 – 15.30: Saray Ayala-Lopez (California State University, Sacramento) – Complaining and resistance (Remote talk)

15.45 – 16.45: Çağla Çimendereli (Syracuse University) – Cognitive Noise and Agency in Nonnative Speaking

Friday, 15th of September

9.30 – 10.00: Meet-up and coffee

10.00 – 11.00: Glenda Satne (University of Wollongong) – Communication as a root form of shared intentional activity (Remote talk)

11.15 – 12.15: Marta Jorba (Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona) – Inner Speech as Mental Action

12. 15 – 14.30: Lunch

14.30 – 15.30: Bart Geurts (Radboud University, Nijmegen) – Normative Agents

15.45 – 16.45: Manolo Pinedo & Neftalí Villanueva (University of Granada) – If infants could speak… From Wittgenstein to Tarkovski

Abstracts:

Francesca Ervas (University of Cagliari)

An experimental study on metaphors and epistemic injustice towards people with mental disorder

It has been argued that people with mental disorders are more vulnerable to epistemic injustice when compared to healthy people and even to people with a somatic disease (Crichton, Carel, and Kidd 2017). Epistemic injustice is defined as the injustice towards a person as a knower by Fricker (2007), who distinguished between testimonial and hermeneutical injustice. Testimonial injustice occurs as a failure to attribute credibility to people with mental disorders due to their social identity and creates a credibility deficit (see also Newbigging & Ridley 2018). Hermeneutical injustice is a failure to recognize the ability of people with mental disorders to make sense of their own experience. Global and local reasons have been provided to explain the vulnerability of people with mental disorders to both kinds of epistemic injustice (Crichton, Carel, and Kidd 2017), with enormous social costs and personal efforts people with mental illness must make to maintain an active epistemic engagement in self-understanding, as well as in the diagnostic and therapeutic processes. Hermeneutical injustice, arising by putting in question their abilities in making sense of their own experience, can generate a feeling of exclusion from the society and healthcare practice itself, since it is precisely a hermeneutical process aiming at reaching shared understanding between patients and healthcare providers.

Metaphors might be a possible “starting point” to foster self-illness narratives (see e.g., Clark 2008), thus overcoming the inarticulacy and ineffability of mental illness experience. Metaphor might be a helpful means to express the “internal life” of people with mental illness which finds no words in plain, literal language (e.g., Mould et al. 2010). Though patients with different mental disorders have shown impaired abilities in metaphor comprehension (Iakimova et al. 2006; Rossetti et al. 2018), metaphor comprehension is associated with highest quality of life in various conditions (e.g., in schizophrenia, see Adamczyk et al. 2016; Bambini et al. 2016). To understand how metaphors used in narrative of mental illness experience affect reasoning about people with mental illness might be a fruitful venue for research, to prevent epistemic injustice.

The talk presents an empirical study which aims to investigate the reasons why participants (N=222) might fail to attribute the intended meaning of the utterances pronounced by people with mental illness, to highlight both the testimonial and the hermeneutical injustice mechanisms, especially in the case of metaphor use. A set of stories were presented to participants to investigate whether and why the use of either a metaphorical or a literal utterance – describing how the speaker (with mental illness vs. physical illness vs. without clinical conditions) feels – might fail to be correctly assessed. Preliminary results of the study show that participant fail more often to attribute the intended meaning to the utterance pronounced by someone who is described as a person with mental illness when compared to the same utterance pronounced by someone who is not described as a person with mental illness, and they fail more often to attribute the intended meaning to metaphorical than literal utterances for credibility reasons. Moreover, when evaluating a metaphorical utterance pronounced by a speaker who is described as a person with mental illness, participants fail more often to attribute the intended meaning because of a perceived lack of coherence and control in the speaker’s behavior.

Rebecca Brione (King’s College London)

Speech Acts, Silencing and Agency on the Maternity Ward: Understanding a Hidden Violation

Vaginal examination is a common intervention in labour. It involves the digital penetration of a pregnant person’s vagina by a healthcare professional, most commonly to assess progress of labour. In England, absent rare and unusual circumstances (such as when a person lacks mental capacity), an individual has an absolute right in law to decline healthcare that they do not want. Maternity policy emphasises the importance of individual agency, and the necessity of birthing people being able to make the decisions that are right for them about what care to choose and interventions to accept. Yet in practice, many people report unwanted and unconsented vaginal examinations during labour – that is, fingers in their vaginas that they did not want, or had explicitly said no to. Some describe these experiences as akin to rape (Brione 2020).

This paper forms part of an explanatory project to understand how such unwanted and unconsented examinations occur, despite the positive legal and policy context, and how they can be prevented. Whilst this is clearly a multi-layered problem, I suggest that speech act theory (Austin 1975) and Langton’s (1993) conception of silencing can help illuminate what is going wrong when a birthing person attempts to say “no” to a proposed vaginal examination. I argue that a “no” should be understood as an illocutionary act of prohibition, with which the birthing person intends to change or clarify the normative landscape such that the healthcarer has an obligation not to carry out the examination. The same “no” has the perlocutionary object of stopping the healthcarer from carrying out the examination.

I argue that some cases in which people say “no” but receive the examination anyway may be understood as instances of illocutionary silencing. To do this, I focus on cases of locutionary success (the person says “no”) and perlocutionary failure (they fail to stop the examination). I suggest that at least some – if not most – of these cases are instances of illocutionary failure, and that many of these will be cases of illocutionary silencing.

In building this argument, I suggest that the prohibitory illocution requires hearer-uptake for success. I argue that this dyadic view of communication can successfully differentiate between cases of perlocutionary frustration (wilful overruling of the “no” by the healthcarer) and illocutionary failure, and has explanatory value in elucidating how and why some speakers “are deprived of agency, autonomy and authority… only because their addressees are inattentive, incompetent or imbued with prejudice” (Bianchi, forthcoming: 7). I suggest that this understanding also directs our attention usefully to questions of what it is about the speaker, hearer or the context which means that hearers fail to recognise the “no” as a prohibition: what it is that renders the prohibition “unspeakable” and the birthing person silenced (Langton 1993: 321).

In the final section, I pose several candidate factors which may explain illocutionary silencing in the vaginal examination context. I also outline and respond to some troubling implications for my account, and consider what they mean for attempts to promote agency on the maternity ward.

Saray Ayala-Lopez (California State University, Sacramento)

Complaining and resistance

I want to reflect on women’s perpetual complaining about household chores. When doing so women are often seen as bitter and disruptive, uncomfortable to be around, frustrated and ineffective. If there is no goal of changing the situation, complaining appears futile and a sign of weakness. Here I want to focus on the tradition of complaining about household chores by working class women, whether alone or in coordination with other women in the same predicament. The uptake complaining gets from the audience undermines these women’s agency and ignores the political import of this distinctive communicative act. I’ll analyze complaining as a form of resistance that doesn’t aim at change and it is only partly justified by the bonding it creates among complainers.

Çağla Çimendereli (Syracuse University)

Cognitive Noise and Agency in Nonnative Speaking

Linguistic justice concerns justice among speakers of different languages and vernaculars. Most linguistic justice theories focus on two questions: How nonnative speaking (of a language or a vernacular) limits effective communication and how linguistic regimes contribute to the hierarchies of linguistic communities in society. However, I argue, there is another important question for linguistic justice scholars which demands questioning the relationship between linguistic competency and thought: How does various levels of linguistic competency affect agency through obstructing thinking. There are many different directions to explore to answer this question, but as a first attempt, I construct and defend the following argument:

- 1) Many nonnative speakers speak with some level of linguistic incompetency.

- 2) Linguistic incompetency causes cognitive noise in the speaker’s mind.

- 3) Cognitive noise may inhibit the speaker’s agency in various ways.

⇒ Therefore, nonnative speaking may involve loss of agency.

First, I explain that it usually takes many years to master a language to the level of native-like competency for people who start to learn the language after their cognitive development. While this process is shaped by many factors such as the learning environment, the language(s) the learner possesses etc., I show that most research in psycholinguistics take the first premise to be a fairly intuitive generalization. Then, I define cognitive noise as a distracting process occupying an agent’s mind taking away from the agent’s attention. In this sense, I argue that when an agent communicates with some level of linguistic incompetency, the use of language itself becomes a struggle which demands a significant proportion of the agent’s attention. I draw from Alshanetky (2019) and Inkpin (2016) who observe that in native speaking, articulation, i.e. putting our thoughts into linguistic form, is usually effortless in the sense that words come to us and we don’t even notice the process of articulation, but in nonnative speaking (even with high fluency) it is usually the opposite — articulation is a noticeable work that we have to consciously take. This is cognitive noise, which consists of deliberately thinking about grammatical constructions and vocabulary, back and forth, such that a significant portion of the agent’s attention is on sentence production and not on many other things available to their perception at the time of speaking, including the content of the speech itself. Finally, I argue that in virtue of taking away from the agent’s attention, cognitive noise inhibits the speaker’s capacity to engage in other mental actions such as inner speech, which has been argued to contribute to conscious-thinking. (Munroe, 2023) This results in agency loss at two levels. First, the agent’s ability to control their own mental life is restricted. Second, the agent’s capacity to exercise certain mental actions, some of them being epistemic actions, is inhibited. Following Fricker (2015), we may argue that this restriction on epistemic actions constitutes loss of agency. I conclude by arguing that this sort of agency loss should be considered as one of the important issues in linguistic justice discussions.

Glenda Satne (University of Wollongong)

Communication as a root form of shared intentional activity

There are many different forms of joint action and shared activity. While some of these require little communication and exchange between participants, communication can make joint action smother and help avoid misunderstandings. But the links between communication and joint action run deeper. Communication itself can be seen as a form of human collaborative activity. A tradition springing from the works of Grice (1957, 1975), and further elaborated by Sperber and Wilson (1996), Clark (1996) and Tomasello (2008), seeks to illuminate the nature of communication as a special form of shared intentional activity by describing the set of special intentional and inferential processes that are characteristic of such form of exchange. Furthermore, communication can be seen as a root form of collaborative activity, one that provides the platform for more sophisticated forms of shared activity as those dependent on sharing norms, instructions or joint practical reasoning. Thus, the ability to engage in simple forms of communication can be thought to be prior in development compared to other abilities for shared activity. In this talk, I explore the social infrastructure of human communication understood as a root form of shared intentional activity. I argue based both on conceptual and empirical considerations, that the traditional view championed by Grice and others is not suited for this task. I end by presenting an alternative inspired by recent philosophical debates on the second person, that challenge the priority of third-personal forms of social cognition -based on observation, inference or theory, and show how this alternative sits within the “minimal collective intentionality” model that I have defended elsewhere ( cfr. Satne 2016, 2021a,2021b, Satne & Salice 2019).

Marta Jorba (Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona)

Inner Speech as Mental Action

The idea that inner speech is something we do, as opposed to a mere vehicle of thinking, is put forward by the activity view of inner speech. This view is congenial to the Vygotskyan approach to inner speech as a developmental outcome in a process of internalization of outer speech and can also appeal to speech production mechanisms to explain its existence. However, the very notion of ‘activity’ in place here remains underdeveloped. In this talk I respond to some problems that have been raised on the idea that inner speech is an action and I propose to regard inner speech as a kind of mental action embedded in an affordance framework.

Bart Geurts (Radboud University, Nijmegen)

Normative Agents

Humans are an intensely social and communicative species, and although neither sociality nor communication is our prerogative, we are unique for the prodigious volume and intricacy of our social interactions and communicative exchanges. We are also intensely normative agents, whose social and communicative interactions are ridden with do’s and don’ts, rights and duties, rules and regulations, and in this respect, too, what makes us special is not so much the fact that we behave normatively, but the sheer extent and complexity of our normative interactions and relationships. The purpose of this talk is to present a framework in which sociality, normativity, and language coevolved, beginning in face-to-face interactions in which our ancestors started treating each other as normative agents and communication became irredeemably normative, and culminating in social institutions that reduce agents to mere role fillers.

Manolo Pinedo & Neftalí Villanueva (University of Granada)

If infants could speak… From Wittgenstein to Tarkovski

If a lion could talk, we could not understand him, Wittgenstein polemically asserted. Nothing is hidden, as a matter of principle, if we share a form of life, if we play the same games, enjoy music together, feel hungry or emotional in similar situations, live by comparable sets of preferences. There are lots that we ignore about everyone else, but we could get to know it. We could come to understand their beliefs, reasons and urges, even if we find them false, ridiculous or contradictory. Non-human animals share enough with us to lead us to feel sympathy for them, to feel obliged to them. But this is no reason to take their mental-behavioural make-up as a gradient towards ours. Infants are no different. And yet, we have been one of them. Is this a question of not remembering what is it like to be an infant? We’ll claim this makes no sense. There are no memories to be had preconceptually. Neither perceptions. In Solaris, Russian astronauts and a clearly sentient planet struggle to understand each other. They fail, and yet, they seem to feel that there is a common dignity, a common recognition of a capacity for love. In Stalker, “the zone” is also trying to reach out to the stalker and other visitors. To be “in the zone”, as much here as in elite sport, is to be in a place that resists being reduced to words or instructions. In this talk we’ll try to account for this paradox, one that involves a moral recognition and an unbridgeable cognitive gap.